Recognizing the Moral Responsibility of Scientific Advancements

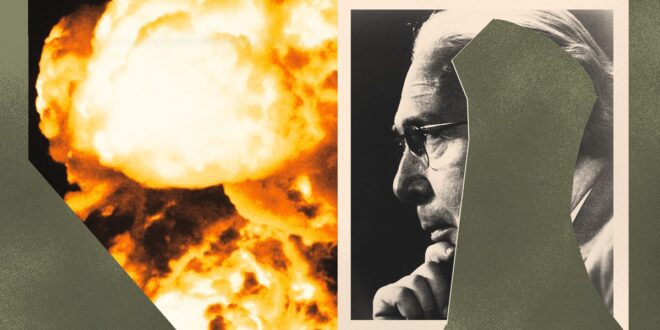

J. Robert Oppenheimer, renowned as the father of the atomic bomb, faced the ethical dilemma of reconciling his scientific pursuits with his conscience. His public expressions of concern about the hydrogen bomb and nuclear arms race ultimately led to him becoming a martyr of Cold War politics. However, Oppenheimer’s stance on responsible science is a lesson that holds true in today’s world of artificial intelligence and genetic engineering. The experts driving revolutionary advancements have both the expertise and moral obligation to help society address the potential dangers inherent in their creations.

Addressing Ethical Questions in Technological Advancements

Research laboratories, whether at universities or for-profit companies, are currently engaged in developing technologies that raise profound ethical questions. For instance, should we genetically engineer plants and animals to be resistant to natural predators, risking the upset of nature’s delicate balance? Should patents be allowed on life forms? Is it ethically sound to “fix” perceived abnormalities in human beings? Furthermore, should we delegate consequential decision-making to machines, such as determining whether to respond to a threat with force or launching a retaliatory nuclear strike? Early nuclear experts, including those from the University of Chicago who initiated the chain reaction, can provide a model for responsible scientific conduct that remains as relevant now as it was in Oppenheimer’s time.

Lessons from the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago

The race to develop the atom bomb began at the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago, where the first self-sustaining nuclear fission reaction took place on December 2, 1942. This laboratory was home to a diverse group of scientists, including Leo Szilard and James Franck. These scientists understood the moral implications of scientific knowledge and firmly believed in its responsible use. The first lesson from the Met Lab was that once scientific knowledge is obtained, it cannot be undone or recalled. Recognizing the world-changing potential of nuclear physics discoveries, Szilard and his colleagues felt a duty to inform the leaders of democracy, leading to the influential Einstein-Szilard letter that urged President Roosevelt to pursue atomic research.

The Met Lab scientists further realized that while scientific discoveries may be irreversible, the effects of these discoveries can be regulated. They sought to shape decisions about the use of nuclear technology during World War II and the subsequent postwar era. The second lesson from the Met Lab was that specific objectives, both practical and noble, could be established to guide the application of nuclear technology. These objectives included giving Japan a preview of the atomic bomb’s power before subjecting them to it, freeing science from secrecy, preventing an arms race, and designing international institutions to govern nuclear technology.

Fostering Public and Democratic Decision-Making

The third lesson from the Met Lab emphasized the importance of major decisions regarding technological applications being made by civilians through a transparent democratic process. In the mid-1940s, Chicago’s atomic scientists engaged in discussions with politicians and public officials, despite the Army bureaucracy’s preference for secrecy. Scientists like Szilard, Franck, Rabinowitch, and Simpson played a pivotal role in educating politicians and the public about the dangers of nuclear technology. They formed associations, wrote opinion essays, and established publications such as the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists to disseminate knowledge. Ultimately, their efforts led to the passage of the Atomic Energy Act, which created a civilian-led agency accountable to the president and Congress for overseeing nuclear science. Throughout the Cold War, they also successfully campaigned for nuclear test bans, nonproliferation compacts, and arms-control agreements.

Applying the Lessons to Modern Technological Advancements

In the 21st century, a significant number of decisions regarding the development and deployment of new technologies occur within private laboratories and corporate realms, away from public scrutiny. This exclusivity inhibits collaboration and impedes the free flow of knowledge necessary for scientific progress. Privatized decision-making undermines the public’s right to participate in ethical decisions through the democratic process. However, the Met Lab scientists believed that such choices should be entrusted to the public. Their template for responsible science should guide us in navigating the ethical dilemmas posed by emerging technologies.

The Legacy of Responsible Science

While atomic scientists, including Oppenheimer, played a key role in the development of the atomic bomb, they also acquitted themselves well by fostering a regime of responsible science. Their efforts ensured that the atomic bomb’s first use in war remains its only use to date. We can learn valuable lessons from these scientists and their commitment to balancing scientific progress with moral responsibility.

Mind Uncharted Explore. Discover. Learn.

Mind Uncharted Explore. Discover. Learn.